Marshallese Perspectives on Migration in the Context of Climate Change

to cite: van der Geest, K., Burkett, M., Fitzpatrick, J., M. Stege, and Wheeler, B. (2019). Marshallese Perspectives on Migration in the Context of Climate Change. Policy Brief of the Marshall Islands Climate and Migration Project. University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Available at www.rmi-migration.com

Marshallese perspectives on migration in the context of climate change

Introduction

The Republic of the Marshall Islands is a nation of widely dispersed, low-lying coral atolls and islands, with approximately 70 mi2 of land area scattered across 750,000 mi2 of ocean (Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs, 2015). Average elevation for the Marshall Islands is approximately 2 m. above mean sea level, and many islands and atolls are lower (Owen et al., 2016). As climate change causes sea levels to rise and weather patterns to shift, the Marshall Islands face flooding, heat stress and drought that damages agriculture, livelihoods, homes and infrastructure (Keener et al., 2012; Marra et al., 2017).

When the frequency and intensity of climate-related hazards increases, residents may have to make the difficult choice of whether or not to leave their home islands in the hope of a more stable future. Marshallese migrants move within the country to larger islands or to the United States of America where the Compact of Free Association allows them to live and work under a special status (Graham, 2008; McElfish, 2016). However, push and pull factors triggering human migration are complex and often intertwined, making it difficult to pinpoint and address specific causes (The Government Office for Science, 2011).

The Marshall Islands Climate and Migration Project1 studies the multicausal nature of Marshallese migration, as well as its effects on migrants themselves and on home communities (van der Geest et al., 2019). It does so through people-centred research, seeking the views of Marshallese migrants and their relatives in the Marshall Islands. The research has a special focus on how impacts of climate change affect ecosystem services, livelihoods and migration decisions. This focus is shown in Figure 1.

Theoretical framework by authors (2017), design by Ryookyung Kim (2019)

This policy brief highlights key findings of the migration component of the research. It presents data and findings on migration patterns, drivers and impacts. It ends with a discussion of the results, with a focus on the tension between being prepared to move and fortifying to stay in place.

Methods

The research team conducted fieldwork with the Marshallese in both the Marshall Islands and in destination states within the United States. The study used innovative social science methods to assess local perceptions of climate change, ecosystem services, habitability and migration. Methods included a household questionnaire (N=278), focus group discussions, Q methodology,2 expert interviews and spatial analysis using GIS.3 The team spent about four weeks in the Marshall Islands’ capital Majuro and two weeks on two outer islands, Mejit and Maloelap. Fieldwork was also conducted in migrant destination areas, specifically in Hawai’i and the Pacific North-West (Oregon and Washington), and lasted three weeks each. The methods and research instruments used in the migrant destination areas in the United States were similar to those applied in the Marshall Islands, but adapted to the local context. For example, while the sampling of respondents was random in the Marshall Islands, the team used snowball sampling to find and select respondents in the United States.

Marshallese migration

At the time of the 2011 Population Census, the Marshall Islands had a population size of 53,158 (2011 Census).4 In addition, 22,343 Marshallese were living in the United States (2010 census). Current estimates of the Marshallese population in the United States stand at just over 30,000.5 This means that more than a third of the Marshallese are currently residing outside of the Marshall Islands. Figure 2 shows the map of Marshallese migration to the United States. Hawai’i, Arkansas and Washington are the most popular destinations for Marshallese migrants.

Figure 2: Marshallese population by U.S. state (2010)

Source: The 2010 Census Summary File 2, Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010. Map by the authors. Note: This map is for illustration purposes only. The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by IOM.

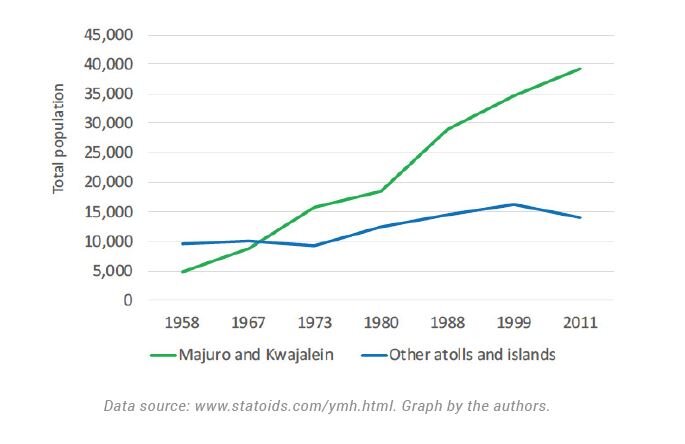

Figure 3: Population growth in urban and outer islands of the Marshall Islands (1958–2011)

However, the Marshallese do not only move to the United States. There is also a large flow of migrants from the outer islands of the Marshall Islands to the urban islands of Majuro and Ebeye. In 2011, more than half (52.3%) the population resided on the capital island of Majuro. By contrast, at the time of the first Population Census (in 1958) less than a quarter of the population (24.1%) resided in Majuro. Figure 3 shows that due to internal migration, the population of Majuro and Kwajalein grew much faster than that of the other atolls and islands.

During fieldwork in the Marshall Islands, the team conducted questionnaire interviews with 199 randomly selected respondents. The survey findings on migrant relatives confirm the high migration propensities of the Marshallese. Almost all respondents (91.5%) had at least one brother, sister, son or daughter who had migrated, and approximately 7 out of 10 (68.7%) had siblings or children who lived abroad, mostly in the United States. The average number of migrant siblings and children per respondent was 3.1. Of these migrant relatives, about half (49.4%) lived elsewhere in the Marshall Islands, and the rest had migrated internationally.

Figure 4: Sankey diagram of destinations of respondents’ siblings and children

A gender breakdown of all migrant relatives shows that 55.8 per cent were men and 44.2 per cent were women, and the figures were similar when looking at only those who moved to the United States: 57.4 per cent were men and 42.5 per cent were women. Arkansas, Hawai’i and the state of Washington were the most frequent international destinations for the siblings and children of survey respondents. Figure 4 shows the destination states of the siblings and children of respondents on Majuro, Mejit and Maloelap.

Drivers of migration

Three sections in the Marshall Islands questionnaire focused on migration, and each also inquired about the reasons why people migrated. One section focused on respondents’ own migration history, the second on siblings and children that are currently residing elsewhere, and the third on intentions of household members to migrate in the next 10 years. In each section, the questionnaire used the same categories of potential migration drivers for respondents to select: work, education, health care, family visits, environmental drivers and others. The category “family visits” involves extended stays with relatives, which often occur in combination with other migration drivers, such as employment or education. Figure 5 shows the frequency of various migration rationales the Marshallese respondents reported (past, present and future). The graph shows that work, education, and family visits are the most common reasons for migration, each being a factor in approximately 40 per cent of the moves. Migration to seek health care is also common but tends to be of shorter duration, which explains the lower number of current migrants who moved for medical reasons.

Figure 5: Marshallese migration drivers in the past, present and future

Source: Household survey. Diagram by the authors, using sankeymatic.com software.

Of particular relevance for this research is the very low number of respondents who mentioned environmental reasons for migration. While respondents expressed concern about the future impacts of climate change on the environment, livelihoods and security of their islands, these survey findings suggest that they do not at present identify these impacts as important drivers of migration.

Arguably, simply asking respondents why they or their relatives migrated does not provide a full and reliable picture of migration drivers (Bilsborrow and Henry, 2012). In the case of Marshallese migration, the dominant discourse is that people migrate for

work, education and health care, and this may be replicated in the answers (see for example, Graham, 2008). In a questionnaire interview setting, respondents may prefer to give the “expected answer” even though they know that the reality is more complex. This study sought to provide a more complete picture of environmental and other drivers of migration by triangulating the findings on cited reasons to migrate with the following: (a) focus group discussions looking at underlying causes of migration; (b) Q methodology studying respondents’ more complex perceptions and opinions on migration, environment, and habitability; and (c) statistical analysis of correlations between a selection of environmental factors and migration propensities. The findings, which are summarized below, confirm that education, health care, work and family networks are the prime drivers of Marshallese migration, but a more nuanced picture emerges for climate drivers of migration.

A closer look at climate drivers

Results from the Marshall Islands abovementioned fieldwork deployed show that respondents identify impacts of climate-related stressors on their livelihoods, health and safety. For example, 92 per cent reported impacts of drought on their households, 47 per cent indicated that they had experienced adverse effects of heatwaves, and 37 per cent had been affected by king tides. Impacts included lack of fresh water, increased soil salinity, damage to trees and crops, adverse health impacts and damage to properties (van der Geest et al., 2019).

Focus groups

In the focus group discussions, participants mentioned the deterioration of “island productivity” as an underlying cause of migration. They explained that livelihood activities on their islands, such as tree cropping and fishing, are becoming less productive because of inter alia increasing soil salinity, and more frequent drought and heatwaves.

Correlation analysis

The correlation analysis below examines relations between several variables, related to climate impact and migration (see Table 1). It shows that for some climate impact indicators, there is a positive correlation with migration rates. For example, households whose house or properties had been damaged by flooding in the past five years were significantly more likely to intend to migrate. Also, households of respondents who perceived that heatwaves and storm surges are becoming worse had significantly higher migration rates. Still, for the majority of climate impact indicators in Table 1, no significant relation was found (unshaded cells with an X).

Table 1: Correlations between climate impacts and migration (N=199 households)

Note: X means there is no significant difference; * means significant at p<0.05 level; ** means significant at p<0.01 level.

Q method

In addition to focus group discussion and correlation analysis, this study also examined climatic drivers of migration through Q methodology. For this, respondents were asked to sort 40 statements on an 11-point scale from “strongly disagree” (-5) to “strongly agree” (+5). Figure 6 shows how respondents in the Marshall Islands sorted the statements on average. Statements situated towards the extreme left and right are issues about which the Marshallese strongly agreed/disagreed. Towards the centre are the statements about which respondents were more neutral. The pyramid in Figure 6 reveals important insights into how respondents perceive the key themes of the research, including the drivers of migration.

According to the average Q sort, respondents perceive seeking better education and health care to be key reasons to migrate. In addition, lack of employment in the Marshall Islands is an important motivation to migrate. A majority of the respondents disagreed with the statement that the quality of life on their island had increased compared to when their parents were young. Dissatisfaction with the quality of life in the Marshall Islands may be an important factor in migration decisions.

The set of Q statements included one statement that directly addressed the question of whether people from the Marshall Islands have already migrated because of climate impacts: “I have never heard of any Marshallese migrating because of climate change.” Almost half the respondents (45%) agreed they had never heard of this.

Almost a third of the respondents (31%) disagreed with the statement, but most “disagree” sorts were under the -1 column, indicating only slight disagreement or even neutrality. Very few respondents (2.7%) disagreed strongly with this statement. Respondents tended to place the “climate migration” statement more towards the centre of the pyramid. This is an indication that they are uncertain whether climate change is already a driver of migration.

Overall, the Q pyramid shows that while respondents do identify impacts of climate change on their lives and livelihoods, the majority resists the idea that their islands could become uninhabitable and that they might be forced to leave some day. The majority believes that between now and a future in which climate change poses a more existential threat to them, there will be solutions.

Figure 6: Q sort grid with the average responses for the whole sample

Source: Household survey. Graph by the authors.

Diverging findings between Marshallese in the Marshall Islands and United States

The Marshall Islands Climate and Migration Project finds an interesting divergence in the reasons that respondents in the Marshall Islands and in the United States cite for migration. Many more respondents in the United States (43.0%) stated that environmental factors played a role in their decision to migrate than those in the Marshall Islands (0.6%). An even higher proportion (62%) stated that environmental factors will play a role in their decision of whether to move back to the Marshall Islands. Marshallese respondents in the United States feared that sea-level rise will make their islands less suitable places to live in the future (van der Geest et al., 2019).

A reason for this divergence in findings between the Marshall Islands and the United States could be that Marshallese people in the United States are more exposed to media speaking of climate change impacts in the Marshall Islands. By contrast, people residing in the Marshall Islands may be not sufficiently aware of the climate risks their islands face.

Impacts of migration

Each section in the questionnaire that inquired about migration included questions on how migration influenced the economic situation and well-being7 of the household. Respondents were first asked to indicate whether the impact was “very positive”, “positive”, “neutral”, “negative” or “very negative”. After that, they were asked to explain why. This was an open-ended question. Figure 7 shows the results for the influence of respondents’ own migration in the past, that of present migrant relatives, and perceptions of future household members’ migration. Overall, perceived impacts of migration were more often positive or very positive than negative or very negative. Respondents’ own migrations (in the past) were assessed slightly more positively than current migrations of siblings and children, but in both cases, the most common answer was “neutral”, which could mean that these migrations had no major effect on the household economy or well-being or that the positive and negative effects were in balance. The graph for future migrations looks different, with more respondents expecting “very positive” and “very negative” impacts when members of their households migrate.

Figure 7: Perceived impact of migration on household economy and well-being

Source: Household survey. Graph by the authors.

Respondents who noted positive impacts primarily mentioned improved education, finding employment, receiving better health care, gaining experience, connecting to relatives and reduced pressure on resources, such as foodstuff and living space. Another positive impact that respondents highlighted was that having migrant relatives makes it easier for the Marshallese to migrate if they want to or are forced to. This is an indication that migration can improve resilience in the face of natural hazards and economic shocks.

The most cited negative impacts of migration were lack of care for children and the elderly, brain drain, adverse effects on development, homesickness and being separated from loved ones, negative experiences in migrant destination areas (such as

unemployment, alcoholism and lack of mobility) and negative social effects related to social cohesion and the Marshallese culture and language. Respondents perceive that many traditional activities in the Marshall Islands are under pressure because of increased outmigration.

Q analysis resulted in three groups with diverging views on migration impacts. The first group are migration critics (43.6% of respondents), who are satisfied with the quality of life, development, governance and security in the Marshall Islands. They think that migration has predominantly negative consequences for migrants, their relatives at home and the Marshall Islands at large. The second group are adaptation optimists (25.5% of respondents), who are quite optimistic that their islands will be able to deal adequately with climate change impacts in the future. They do not oppose migration, and think it can be part of the solution, but they do think that migration adversely affects Marshallese culture. The third group are the island pessimists (14.9% of respondents), who are clearly dissatisfied with life in the Marshall Islands and have a strong desire to move to a different place, preferably the United States. Respondents in this group are very negative about changes in the quality of life, governance, development and livelihood security in the Marshall Islands, and they question the future habitability of their islands. They see migration to the United States as the best or the only option, emphasizing the benefits of migration and downplaying adverse effects.

Combining data from the household survey with data from the Q methodology makes it possible to analyse the socioeconomic characteristics of the three Q groups. The migration critics had, for example, received, on average, the lowest amount of remittances from migrant relatives, which may explain their negative view on migration. The adaptation optimists were significantly younger and higher educated than the other two groups, which could mean that a new generation, who believes that there are in situ adaptation solutions to climate change, is emerging. Among island pessimists, most had a medium level of education (secondary school), which may have contributed to their discontent about life in the Marshall Islands, as they do not have enough formal education to get a salaried job in the Marshall Islands, while they do have knowledge about opportunities abroad.

The Q analysis shows that one can distinguish differe

nt views on migration and future habitability within the population of the Marshall Islands. This is important for policymakers, as people in these groups may respond differently to migration and climate change adaptation policy.

Conclusion

The case study findings illustrate an existential dilemma: on the one hand, it is important to be prepared for a future in which islands may become uninhabitable, and to make sure that migration and relocation can take place in an informed, orderly manner that minimizes loss and damage.8 On the other hand, suggesting migration and relocation as solutions is extremely sensitive as it suggests giving up on the islands.9 A majority of the survey respondents think that it is too soon for this, and that there is still much uncertainty about the future impacts of climate change and the capacity to adapt locally. However, as this study also shows, there might be a middle ground. Voluntary migration is already happening at a rapid pace today, and new Marshallese communities are emerging in the United States. The current migration experience that Marshallese people are gaining and the migrant networks they are building can become an important resilience asset in the future. Migration outcomes tend to be negative when people are forced to migrate or are displaced without enough time to adequately prepare. The Marshallese migration experience and networks can facilitate future migrations in the context of climate change that are more pro-active and planned and less forced.

FOOTNOTES

1 See more information on the Marshall Islands Climate and Migration Project here: https://rmi-migration.com/

2 Q methodology investigates opinions or “shared views” on a particular theme by analysing how respondents rank a set of statements from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”.

3 The methods are described in more detail in van der Geest et al. (2019).

4 Economic Policy, Planning and Statistics Office, Office of the President, The RMI 2011 Census of Population and Housing Summary and Highlights Only. Available at www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/migrated/oia/reports/upload/RMI-2011-Census-Summary-Report-on-Population-and-Housing.pdf

5 A detailed calculation of this estimate is available in van der Geest et al. (2019).

6 See www.statoids.com/ymh.html

7 The questionnaire did not give a specific definition of well-being. The answers to the open question, in which they explained their selection, do reveal what aspects of well-being they valued.

8 This point has been made in earlier papers, such as Burkett (2015), Stege (2018) and Oakes et al. (2016).

9 This point has been made in earlier papers, such as Barnett (2017) and McNamara and Gibson (2009).

References

Barnett, J. 2017 The dilemmas of normalising losses from climate change: Towards hope for Pacific atoll countries. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 58(1):3–13.

Bilsborrow, R.E. and S.J. Henry 2012 The use of survey data to study migration–environment relationships in developing countries: Alternative approaches to data collection. Population and Environment, 34(1):113–141.

Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs 2015 U.S. relations with Marshall Islands. Bilateral relations factsheet. Available at www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/26551.htm

Burkett, M. 2015 Rehabilitation: A proposal for a climate compensation mechanism for small island States. Santa Clara Journal of International Law, 13(1):81–124.

The Government Office for Science 2011 Foresight: Migration and Global Environmental Change. Final Project Report. London.

Graham, B. 2008 Determinants and dynamics of Micronesian emigration. Background paper to the Micronesian Voices in Hawaii Conference, April 2008.

Keener, V.W., J.J. Marra, M.L. Finucane, D. Spooner and M.H. Smith (eds.) 2012 Climate Change and Pacific Islands: Indicators and Impacts. Report for the 2012 Pacific Islands Regional Climate Assessment (PIRCA). National Climate Assessment Regional Technical Input Report Series. Island Press, Washington, D.C.

Marra, J.J. and M.C. Kruk (coordinating authors), M. Abecassis, H. Diamond, A. Genz, S.F. Heron, M. Lander, G. Liu, J.T. Potemra, W.V. Sweet, P. Thompson, M.W. Widlansky and P. Woodworth-Jefcoats (contributing authors) 2017 State of Environmental Conditions in Hawaii and the U.S. Affiliated Pacific Islands under a Changing Climate: 2017. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information.

McElfish, P.A. 2016 Marshallese COFA migrants in Arkansas. The Journal of the Arkansas Medical Society, 112(13):259–262.

McNamara, K.E and C. Gibson 2009 “We do not want to leave our land”: Pacific ambassadors at the United Nations resist the category of “climate refugees”. Geoforum, 40(3):475–483.

Oakes, R., A. Milan and J. Campbell 2016 Kiribati: Climate Change and Migration: Relationships Between Household Vulnerability, Human Mobility and Climate Change. Report No.20. United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security, Bonn. Available at https://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:5903/Online_No_20_Kiribati_Report_161207.pdf

Owen, S.D., P.S. Kench and M. Ford 2016 Improving understanding of the spatial dimensions of biophysical change in atoll island countries and implications for island communities: A Marshall Islands’ case study. Applied Geography, 72: 55–64.

Stege, M. H. 2018 Atoll habitability thresholds. In: Limits to Climate Change Adaptation (W. Leal Filho and J. Nalau, eds). Climate Change Management. Springer, Cham, pp. 381–399.

van der Geest, K., M. Burkett, J. Fitzpatrick, M. Stege and B. Wheeler 2019 Marshallese migration: The role of climate change and ecosystem services. Case study report of the Marshall Islands Climate and Migration Project. Available at www.rmi-migration.com